|

From the Night Factory

22. A Misadventure

Ms Keogh, my more significant other, is the all-consuming joy of my life, my greatest happiness and single most important reward for whatever it is I did to deserve her, but I cannot imagine how it is I deserve her. As a consequence of this, the single worst tragedy in my life would be losing her, which, as intolerable a thought as that is, is a real possibility. The downside of any relationship is that one party is likely to outlive the other. We met in 1982, have been together since 1983, and in about another week will have our 26th wedding anniversary.

Ms Keogh has chronic renal failure. She was on dialysis for over 19 years. The first two kidney transplants were immediate failures, but the third one served her for the last six years, until recently. Due to complications, conflicts between medicines, her present transplanted kidney has begun failing. It is probably only a matter of time, a short time at that, before she will return to dialysis.

Ms Keogh is a retired Physician’s Assistant, a midlevel practitioner of medicine specializing in diagnosis. She has always impressed upon me the importance of getting immediate attention for a stroke, that recovery is more likely the sooner it is treated, and much restoration can be achieved if physical therapy follows quickly. Perhaps I learned this lesson too well. More likely I didn’t learn enough.

On this particular night, Ms Keogh was unable to sleep. She developed a severe headache. Also, her teeth were hurting and she felt nauseous, symptoms she thought could be a cold coming on. Her remedy was to take two super-strength Tylenols and then she climbed back into bed. It was ten o’clock on a Saturday night. I was keeping her company, sitting at the small desk in the bedroom watching “Up with Chris Hayes” on the internet. She did not sleep soundly. Every once in a while she would make a remark to me about the program; she was drifting in and out of sleep.

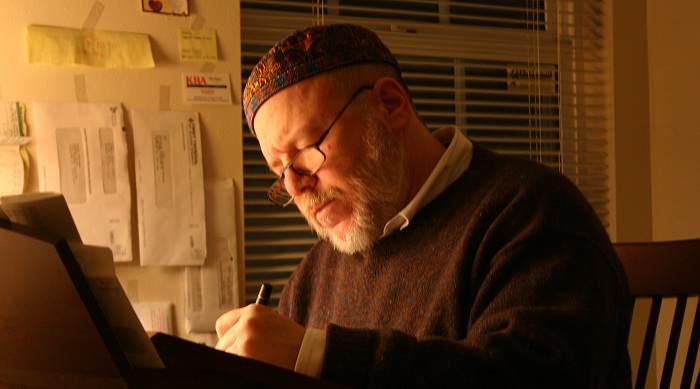

When the program concluded, I moved into the dining room and wrote letters at the table. The bedroom door was opened and she could watch me. At one o'clock in the morning, still unable to sleep, she climbed out of bed and joined me at the dining room table, vexed and grumpy. At least her headache was vanquished, but she was desperate for sleep and she was also hungry.

I set before her a bowl of cantaloupe chunks. Surprisingly, she consumed nearly all of it. Her appetite was healthy.

While I continued to write letters, Ms Keogh opened her VAIO netbook and began playing backgammon. All was fine until I noticed her eyelids were drooping. I thought she had fallen asleep in the middle of her game, but when I asked, she was awake and told me so.

Then, at about one:thirty in the morning, she began asking me strange questions about the backgammon board, wanting to know why the color had changed. I rose from my seat and stepped alongside her to view the netbook’s screen. I did not detect anything different in the colors of the backgammon board and pieces. Still, she continued to complain that the board and pieces were different and she couldn’t work it out. She put forward strange questions; why were there dots on the counters and why weren’t they on the die? Whatever it was she was seeing, I was not seeing the same. She kept repeating her question, all the time smiling at my confusion, and she started slurring the words. This was the moment I began to suspect my cherished companion had had a stroke. I could think of no other explanation, all I could be sure of was something was definitely wrong neurologically.

I asked her, who was the President of the United States? I had learned the value of such a question from her. She laughed and would not answer. When I pressed for an answer, she declared “twenty-five”. It was as if she was trying to avoid answering just to be funny, just to annoy me, the way my father did when he had his stroke. My father had behaved as if the answer was too obvious and responded with jokes, laughing like a drunk at his own silly answers, but when he finally did make a serious attempt, having gained the time to ponder the question, it was the wrong answer. In Ms Keogh’s case, she finally said Barack Obama. I next asked her to tell me the date. She said the 26th. I thought this was close enough, as it had been the 26th just an hour and a half before. That was the last of her rational conversation that night; she began talking in non sequiturs.

My dilemma was this; I depended on Ms Keogh’s vast diagnostic skills to tell me what to do in any medical situation. She was unable to advise me. So I did what comes naturally to me; I panicked.

I told her to get dressed. She would not stop staring at the backgammon board on her netbook trying to make sense of it. She asked why did she have to get dressed and I explained that I was taking her to the emergency room at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, a distance of about 28 miles into the heart of Philadelphia. This is where all the doctors and specialists that tend to Ms Keogh’s health converged. This is where they knew her and the particulars of her illness. But she did not want to go, and in a soft, whiny voice refused. The very softness of her tone added to my concern. It was not the midlevel practitioner of medicine defiantly instructing me in declarative statements of confidence. She offered no explanation for her resistance, except that she just wanted to go to sleep.

I was confused by her resistance. Being ignorant of medical matters, I lacked confidence as to how to proceed. Was I to physically wrestle her into a blanket and carry her downstairs to the car? I threatened to call 911. She asked me why, so gently and confused. I kept repeating how I thought she was showing symptoms of a stroke and I submitted my observations, but she couldn’t understand my reasoning, merely pooh-poohed my analysis. “Just let me sleep,” she said in a muffled voice, “and you can take me in the morning if I still show the symptoms.” I should have followed her advice, but I can only say that with hindsight.

Scared, I searched the internet and called the first hotline I found, but they only attended to emergencies in California. I called the Jefferson nephrology hotline, which was a desperate act because I didn’t feel it was appropriate, the symptoms having nothing to do with her transplanted kidney. The hotline said they would have their on-call doctor call me back. Hadn’t Ms Keogh taught me the urgency of dealing with a stroke? I couldn’t wait. I called Jefferson’s emergency room and they put a doctor on the phone. I reported the symptoms I’d observed, the earlier headache and nausea, the drooping eyelids, the slurring speech, and her inability to reason. The ER doctor said to bring her in to be evaluated. Then the nephrologist called back. I repeated my story. She asked me one key question, had my wife taken any drugs. I said no, none outside of the ordinary regimen required, with the exception of Tylenol. Ah, but it was exactly on this point that I was not well-informed. I lacked crucial information. The nephrologist gave the same advice as did the ER doctor.

These telephone conversations unfolded while I sat on the edge of the bed. I hoped Ms Keogh was aware of every step I was taking so she could counter it, if need be. At this point she gave no resistance. How could she, she was three-quarters asleep and didn’t care that I was next calling 911. Her not caring struck me as symptomatic of the problem. It was not like her to not resist with intelligent argument.

It was hard to find our apartment among so many look-alike buildings in this development. I stood out on the hallway balcony, cold with winter, and waved to the two paramedics when they arrived. Two flights of narrow stairs, no elevator, it must have concerned them as they made their way. The apartment was a distressful mess, a very narrow lane between boxes in various stages of being filled, most of our possessions spread out for consideration. We were about to move to another apartment. It didn’t upset Ms Keogh that two unknown people had appeared in our bedroom, were leaning over and questioning her as she was trying to sleep. She merely smiled and asked, “Who are you and what are you doing here?”

They were getting the same argument from her that she gave me. She refused to go. To make matters worse, they would not take her to Jefferson, only to Saint Mary Medical Center. Saint Mary was a mere five miles distant and has an excellent trauma center. Our reluctance to use Saint Mary was merely because Ms Keogh’s particulars were established and better understood at Jefferson. But it was too late, she had squandered the chance to go to Jefferson when she forced me to call 911.

At first they agreed and believed it to be a stroke, but as they examined her more thoroughly than I knew how to, inconsistencies appeared. Both of her eyes were drooping, it was not just on one side. The paramedic had her hold both arms out and resist his pressure to force them down. The strength was equal in both arms. Then they asked if she had taken any medication – the other paramedic was already listing all the medications he could find, nine different active prescriptions and more on standby. She told them she had taken two Ambien to help her sleep, twice the dose she usually took, although “usually” does not apply because she took it so rarely. This, I didn’t know. Nor did I know until the paramedics explained it, that what we were witnessing could also be explained by the Ambien. The more they questioned her and examined her, the more convinced they were it was not a stroke, yet they still wanted to take her to the ER for a proper evaluation, especially since doctors had already instructed me to take her. They didn’t want to override any doctor’s authority and be wrong.

It took a lot of arguing, threats, and negotiating, but finally she agreed with great reluctance and under protest. It was not as vehement as it could have been. She also insisted that I drive her and not have her travel by ambulance. Groggy, she dressed and walked out of the apartment under he own power. During our drive, she repeatedly interrogated me as to why was I doing this, why did I think she was having or had a stroke? I told the story multiple times, yet a minute after she would forget and I would have to tell it again.

I brought her to the emergency room of Saint Mary where they were expecting us. I saw her admitted and then went to park the car away from the ambulance lanes. A large deer had left the adjacent park to feed on the garden of one of the hospital’s outbuildings. Majestic and wary, he lifted his head to stare in my direction as I stared back. I was feeling relieved about Ms Keogh. If it was a stroke, she would not have demonstrated the equal strength she had in both arms. It would not have been both eyes that were droopy and both corners of her mouth. That was what I was telling myself. It was just the Ambien, most likely. Of course, I didn’t know for sure that it was, but she was safer at Saint Mary than she would have been alone in my care. For all my hope, boy was she going to be pissed with me later, after she had slept off the effects of the Ambien. Had I just left her to sleep, it might have been all the cure she needed.

I joined her in a private stall of the emergency room. I watched over her the rest of the night, chastising myself for this incompetence. They had inserted an IV. They did an EKG. They x-rayed her chest. For each procedure she woke briefly, smiled and laughed, saying “sure” to every request.

A nurse came in with antibiotics. What was this! The nurse explained that Ms Keogh had pneumonia. I did not have the skills to be a patient advocate, yet told the nurse not to give Ms Keogh the antibiotics. I knew she didn’t have pneumonia. The nurse said she would have the doctor come in and explain it to me. I knew it was a misdiagnosis, something to do with scar tissue they found present in her lungs, but it had already been dismissed by the pulmonary team at Jefferson. But as a layman, I was unable to explain my bits and pieces of knowledge to the doctor when he arrived. He merely saw my ignorance. He further explained that they would have to admit her because her heart rate was too fast, she had atrial fibrillation, and her potassium level was too high. I spoke without obvious authority on the subject. As Ms Keogh would say, I lacked med-speak. I argued that they would not admit her, that all these concerns were being monitored by the doctors at Jefferson.

Thank goodness, it was at this point that Ms Keogh partially woke, and she, even in her half-sleep, brought all her authority to bear, was able to detail how the changes in her lung were the result of an obscure allergic reaction to one of the immunosuppressant drugs she had been taking.

Despite the doctor’s wishes, Ms Keogh signed the necessary waivers, and we escaped the hospital. The sun arrived as we drove home. She went directly to bed. And I went to sleep alongside her, comforted in the knowledge that I would continue to have her companionship, despite my fears that she would bully me for my stupidity once she had slept and returned to normal.

No such reprimand took place. She told me that my not knowing about the Ambien made my reaction forgivable, though she could wish my medical acumen had been better. More importantly, she explained, she was hardly aware of what was going on, the entire experience was relatively painless and dreamlike. Indeed, she described her behavior and efforts at communicating with me no different than sleepwalking. She had absolutely no memory of any of the procedures the hospital put her through. She said she found the entire episode a comic misadventure and an act of love, “but next time ask me if I’ve taken any mind-altering substances.”

Mr

Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about

the events and

concerns of his life. If you've any comments or

suggestions, he

would be pleased to hear from you.

Mr Bentzman's

collection of poems "Atheist Grace" is

available from Amazon, as are "The Short

Stories

of B.H.Bentzman"