|

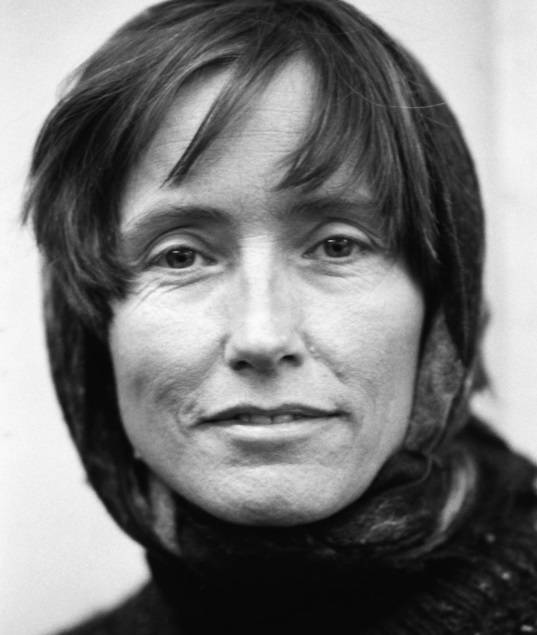

81. May the Memory of Her Be a Blessing

Ms Barbara Anne Keogh, died Sunday, 17th June 2018. She was my cherished companion for nearly thirty-five years, my wife for thirty-one. The day before, she had suffered cardiac arrest for eight minutes. The heart beat restored, she never regained full consciousness, her jaw was pulled open, her cheek pulled down, were no longer resisting gravity. I did not want others to see her this way, remember her this way.

What is the value of erased memories? We are our memories. We fall back on memories to define ourselves. Sometimes for comfort, like home movies or vacation slides. Then there are the things we tell ourselves we must do before we die, as if we can collect a bundle of memories to take with us to an afterlife. My cherished companion and I did not believe in an afterlife. Where are the places we’ve been together and the things we did together? In my memory yes, and in the memory of friends, but no longer in hers.

Her death was both expected and unexpected. She was a retired Physician’s Assistant, a midlevel practitioner of medical science, and she knew her life was drawing to an end, she knew and prepared me for it. Every time she went into the hospital, we realized it could be the last time and we were continually stunned with our luck. She went into the hospital early on a Thursday morning. The antibiotics and pain medicines brought her quick relief and the cellulitis was in retreat. No longer distracted by pain, her wit and charm were restored. We thought we had been lucky once again.

Luck came to an end early Saturday morning. I talked to her even though she gave no indication of consciousness, even while believing she couldn’t understand me. I told her, “I am ready to do it all over again, marry you again, go back to work for AT&T, help raise the children. I will go back to our poverty and debts. All the commutes…” and then my words ran out. So I sang, just a few of our favorite songs, old jazz standards, and I think she reacted or it was a coincidence.

I was not to see my cherished companion dying comfortably in her sleep with a smile left on her face by the departing soul moving to a better life. She did not die in her sleep. She reacted to the voices of her older brothers and woke partway from her prison. She died giving the appearance she was striving to comprehend or was desperate to communicate. Then she turned to me, but I don’t say she saw me. I saw the pulse quit in her neck, the pulse I had for years previously searched for hundreds of times when I thought she was too motionless in sleep. She would sometimes wake and reprimanded me, why was I studying her that way? She would say it was creepy and order me to stop it. I would turn away and go to sleep or back to my desk, nevertheless satisfied.

Must I remember for the rest of my life seeing her at the moment her pulse stopped? I moved from the foot of the bed to where I could stroke her head and kiss her brow. Her body took a few determined gasps and next I heard that notorious death rattle about which she had taught me. She was gone, her skin turning grey, gone from all existence and beyond any dream of reuniting.

Was it the next day; was it the day after that? Coming back from errands to buy fruit, salad, and a loaf of bread, I opened the door of the flat and saw down a short hall into the bedroom. The side of the bed closest to me, the side on which she slept, was deserted, and a wailing volcano tried to rend my chest. I choked it off, at least until I could close the door of the flat, lock it, and move a distance from it. Then I permitted myself to cry again.

The crying comes in waves and I am never sure what will prove the catalyst. Wandering outside becomes a risk that something unpredicted might provoke a bout of sobs or weeping. I don’t want the attention of strangers. I don’t want to explain everything again. I avoid the places where we are known and they will ask, “How’s your wife?” I want to be alone in the flat where the tangible essence of my cherished companion still lingers. I require it.

For the first few days there was her mess, the dirty clothes on the floor and the piles of papers on her desk. Bags and boxes of unfinished projects lined the walls. Two of my sisters-in-law aided me in a triage of Ms Keogh’s belongings; to go to family, to friends, to charity, or to be discarded. We found a shoebox and inside were the new shoes she bought the week before. She never got to wear them.

There were many good omens before her death that made us think things were getting better. I had just found her Dantrio "Brillante" rollerball, her favorite pen, the black barrel inlaid with panels of abalone. It had been lost for a year. She was overjoyed to have the pen found, but a week later she died.

We were in awe of her hair. It was something neither of us could explain. Her hair had been growing thinner for years and in patches she was beginning to appear bald. She began cutting her hair very short. This last winter, she bought a wig. I hated that wig. Then came the miracle, her hair began to rapidly grow back. Not just grow, but it was thicker than ever before in life. It was also wavy. She had always hated her straight hair. It was the color she wanted, grey and silver and not her former mousy brown. It began to be too long and unkempt. A few days before her stepmother visited, she had it trimmed. A week later she died.

She went into the hospital with plans for things we would do together when she came out. She loved road trips. Just days before she went into the hospital, I had succeeded in securing a British driver’s licence. She had a list of places to go with a rented car, but this time she never came home from the hospital.

I am fortunate in having an abundance of friends, both here and abroad. They have all offered help, asking me to call, some saying they wanted to come and comfort me. It is my nature that I would rather be alone with my thoughts and confront the void until I can deal with it. I still take comfort from being in this flat, in this city, and in this country because they all embody her. She and this place are related to each other. Fifty years she wanted to come home to Britain.

She was my single greatest source of happiness. I am distraught because the conversation we were having was never completed. Still, I don’t want friends to worry about me. No one says the word “suicide” within my hearing. I suspect at times my friends and in-laws have me on suicide watch. I am confident I won’t kill myself. I will leave it to nature to do it for me. Meantime, there are frequent calls and requests to come out for coffee. I don’t mind. Since moving to Wales, these new friends and this new family are very supportive. While they closely watch over me, they also understand my need for privacy, to grieve without an audience. I am going through what many people must go through. It feels impossibly hard. I am being catered to by good friends and dear in-laws. I have been extremely fortunate in the company I keep.

I will have to continue to live for maybe another twenty years without my cherished companion to embrace, to not bury my face in her neck, to not be able to stretch out my hands to meet hers halfway across the table whenever we dined out, to not have her stroking the back of my head as we snuggled on the couch. In bed, asleep, we sometimes held hands.

To begin life again? It is an entirely new life I need to adjust to. There are stories, common enough, of survivors dying of a broken heart soon after the death of their spouse. If that happens to me, I am okay with it.

The rest of my life suspended before me, time to fill with whatever I want, but the reality of her not being in it is impossible to believe. Every new experience is what she has missed and I crave to tell her about it.

I no longer enjoy things with my former gusto. I think how she is missing this and then I miss her. My melancholy is a profound indifference that infects everything that used to excite me. This sadness is inexhaustible.

President Trump is helping me to deal with my tragic loss. Outliving the ones we love is a commonplace hardship. Many will experience it and it would be a conceit to think misfortune is unique and distinguishes me. Thinking about the children torn from their parents and placed in concentration camps by Trump’s command, it puts my unhappiness into perspective. My sadness is trivial.

The funeral was on a Friday, 6th July, and went exceedingly well, near exact as to how Ms Keogh envisioned it, I believe. There were neither mistakes nor misfortunes. Many good memories were created that day, yet even as I could recognize the success of the funeral and the reception, it tore open the wound and I lost her again.

I went alone for dinner at Café Rouge. The hostess greeted me with surprise, “Dining alone tonight?” Yes. Then the other waitress, the one from Turkey that Ms Keogh and I enjoyed chatting up, came over and asked, “Where is your beautiful wife?” I told her, then lost control and embarrassed myself. They quickly took me to a table away from others so I could have some privacy. I brought myself under control and ordered wine and dinner. They wouldn’t let me pay.

On 16th July, a day shy of it being a month from her death, I visited her grave for the first time since the funeral. The grass had not grown back. Wales has been suffering an unusual heatwave. There was still a mowed trail leading to the burial. The site was a pronounced mound of disturbed dirt. I cried again.

The mound held many plain tan stones. Plenty of them had been broken by the heavy equipment used to dig then fill the grave. The exposed parts of broken stones revealed in sunlight a beautiful green rock speckled with stars. One stone had been sheared on two sides leaving it a thin slab small enough to rest on my palm and outstretched fingers. I took that stone away with me, the opposite of what I usually do at cemetery visits. A memento, I guess. I brought the stone to Andrew Haycock, Curator of Mineralogy and Petrology at the National Museum Cardiff. He identified it as Micaceous Sandstone from the Devonian Period. This stone with its mica stars resides at my desk. I have yet to decipher the message this stone has for me.

On Saturday, 28th July, unable to sleep the night before, I visited the burial again at 7:30 in the morning, which is fortunate because there was no one about. Bawling uncontrollably, I was joined by the weather, a violent wind accompanied by a sudden soaking downpour. As I left, drenched to the skin, I thought of how Ms Keogh would mock me for the tragic-romantic figure I presented in the rain. It caused me to laugh at myself even as I was crying.

This is difficult to explain. There have been times in the last year or two when Ms Keogh had too much difficulty rising from her seat or from the edge of the bed. I would help. She would look up at me with a childish grin, spreading her arms wide, an invitation to be lifted. When this happened in the hospital, she would dismiss professional assistance from the staff preferring it to be me. “I’ve got this,” I would tell them. I would bend at the knees to lower myself and we would embrace. We would rise together, standing entwined, me breathing in the scent of her neck and she affectionately clinging. Everything had to wait as it took a moment before we would release. Should at times I think of her, this is the vision that comes most frequently; she is looking up, that frivolous grin, her arms outstretched, and I desperately miss her.

There remains her scent. I have not yet changed the sheets on our bed.

![]()

Mr Bentzman will continue to report here regularly about

the events and concerns of his life. If you've any

comments or suggestions, he would be pleased to hear

from you.

Selected Suburban Soliloquies, the best of Mr Bentzman's earlier series of Snakeskin essays, is available as a book or as an ebook, from Amazon and elsewhere.