The Ladykillers are Somewhat Overrated

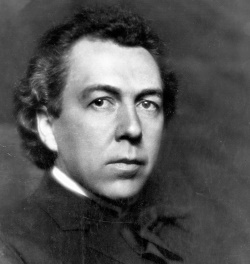

A study in Ted Hughes, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Charles Lindbergh

I.

If they’re wrapped a little too tightly, an unsprung

coil, a garden hose in any Girl-Next-Door’s or yes

prison yard, any small thing held tortuously aloft

in bell jars or cabined up in Fourth of July wrappers,

they’re gunpowder in a quiet muzzle, any firecracker

that might be a dud, you’ll like that, Ted. Wrap it up.

You’ll take it. Those monarch wings, just pinned,

never spreading on your watch. A little match is

all it takes. Butterflies are stupid things anyway,

blooming out of awkward ugly stages, wormy, short-

lived, and they leave traces on your hands once

you’ve caught them. It’s revenge for the touching, the

residue, that leads you both to the gas, isn’t it? The

killing space, charnel kiln, and just like gunpowder

these traces of flesh will bond to fingers, these

hands garroting groom’s tie, knotting the noose over

your throat, to grace every word Sylvia ever wrote.

They’ll knit your socks, your sleeves, smoothe

your collars with a murderous hand, and breathe,

yawn, take in your other wife with Sylvia’s glass

in her paws, looking at you, your scrawny lines,

mewling discontents, and all, all, will leave you.

Sylvia will leave her children with milk and their

cereal, Ariel having sealed them off from fumes

like ovens or your poems, or the rumors of your

dismal affairs and sordid self-love. Some tape

outside their doors like Passover blood blocked

this all. But your other wife, with Sylvia’s brush

in her hand, her robe cocked over her shoulder,

says of you, Ted, “In bed he smells just like a

butcher.” In your bed, two days after Sylvia died,

this is what-will-be-your-new-bride said. In her

bed, this adhesive works in reverse, pinning her

to earth, your last trinket taken, death’s afterbirth.

II.

You lay all things horizontal, so nothing soars.

The concrete you pour is all break-your-mama’s back

of five squealing children. You couldn’t be bothered

with all these good designs squandered, with her,

with them. You built a vaulted playroom way up top

and moved your own mother in next door, to clapboard

yellow rising those three stories above you, looking

down, like Victorians will do. You shut the kids up like

caged birds, because good children are seen, never

heard. They see you, though, these kids, provincial oak

pillars of this grim society, original censors, unbending,

demanding, vile, unyielding, spurning your work.

That town, your drafting tool, a harsh writer one day

will call a place of wide avenues and narrow minds.

You will steal from your mentor, take sly sidework,

trace his designs and call them all your own while he

pays the mortgage for your mother to torment your

wife, fomenting grief all along your low-browed roof.

You’ve left them no firewood stored against winter.

When your client at Robie House calls you, miserable

in her marriage, miserable with her drainage, with

a leak over her chair because you, theoretical

engineer, don’t reinforce anything, since truth told, you

take geometry’s clarity for structural stability,

convenience for comfort when it’s all just stiff as hell,

true to form quite curtly say, “Ma’am. Just move your chair.”

She lived fourteen months there, in your bricked-in

bunker, hunkering down where your forms failed you.

And after many months of spastic construction, your

temper-fits, an ad-man bought it next and died, and then

it went to a man in trade. None lived in it longer than

a decade, in a time when folks did. It passed to rowdy

fraternity men, and then the seminarians prayed to

finish it off. When the wrecking wheel came, you

were 90 and said of your gaping-maw basement, that

subterranean drawbridge to Levittown and the vaunted

doomed American Century, “This goes to show the danger

of entrusting anything spiritual to the clergy.” Well,

they didn’t end you that day, did they? Dorms bloomed

for God’s dowdy clarions right in Mrs. Robie’s backyard,

instead. That’s what prayer’ll get you: a view of

the squat thing we’d all wreck if wrecker could.

What did you ever rightly finish, Frank? Your Robie

is a dismal, low-slung thing on a cooked plain without

light, a prairie of paving stones even then, with no sky

in sight. Its privacy skulking from basement entry,

its buttock-punishing furniture unlivable, its tiny

eyes massed on a scale just enough to shrink Missus

or make her crazy in the blighted light of Chicago

at any time there, with just the tap of rainwater over

a chair. You never finished anything, Frank, except

Kitty, the kids. Mr. Cheney hired you to build a house

for his old-school brood, and you guilded a low,

sloping elopement with his wife. You visioned her a house,

next, that in a Welsh tongue means poet, magician,

priest, tended and spurned by the unfaithful servant, your

Taleisin. It was burned over the heads of this your

mistress, her dismal brats, but you were away. No axe

or wrecking ball or cocktail of carbolic acid came for you

that day. But you, stubborn hierophant of alphabet blocks,

your mother’s son and man to no other woman, went back

to her Spring Green and took her money again, and

rebuilt, resurrected your Taleisin. And like every yearned-for

obsolescent Victorian tinderbox you torched, leveled, wrecked,

ruined by adjacency to your ground-hunkering rhombuses,

it burned. Your aching scorched earth, you built it all, all,

tire/some-lessly over again, and raised another child,

shame/ful-lessly, seamless as dreams, no flagstone to these children,

the women who bore them, bore up under your crushing plans,

as though the draftman’s hand rendered you blameless.

III.

Anne Morrow gripped the deathstick of joy in these surreal

ethereal planes you once crossed and pronounced you a

chiseled face, a human cathedral, a chordstrike of grace.

It went downward from there, of course, in a long spiral

like the gifts from the sea she collected, each conch just the

knuckles on your hand gripping the controls of an ill-

tilted machine. Did she know, Lucky Lindy, the one

tumbling moment when an embrace becomes a slur, that

lilting tilting wing that belongs to the one bird way up high

that is unsinging herself, her little chest puffed up with her

pride in you as your little temple busily desecrated itself?

You said it yourself, in an engine against the sky you looked

down on earth like God, strode this narrow world like the

colossus Augustus you were. You, Aryan peacock, would

let her clock 40,000 transatlantic miles with you, even for

awhile knocked-up, and then you’d knock her back with

a smile while she listened for wind or the Orient force of

your contempt. Her father, from the House of Morgan, the

well-walled plaza of cozy wealth, loved his children best.

Your bigamous grand-dad, though, left his clan, made you his

pride. He gave you a lean jaw, a trim fit, a certain gaze.

For those he left, wife in an old country or farmhouse,

a chintz curtain flapping like a funeral shroud in the wind,

your Anne was straining to hear. Her buzz is distant, dismal

in your ear, the whine of all mothers, all the instruments

of rote creation. He stole you from that woman, your wife, as

surely as the surgeon wields the knife on all the ancient pain.

What did old Bruno Hauptman take from you, American

Augustus? Anne went down from the nursery because you

would be so, so angry at flying alone again over dinner, and

your misery never was solitary, was it, craving intercontinental

company. Anne would remember later a sickening thud that

must have been your Junior falling to dirt from the window.

40,000 miles, 50,000 dollars later, you wrote your autobiography

of values on Anne’s face, she who loved yours. It’s all a ransom

deal, isn’t it, anything hardening our souls to earth, tying us here

to these women, these withering brats, these nasty stormclouds

of domesticity. They found him just a little bit away in a grove,

your Junior, not far from this house you had made with Anne.

You named your next children, quite literally, Reeve and Land.

They are tethered to this earth of Anne’s shifting sand, not

ambassadors, not presidents, just the dull sedimentary

relief of it all. Anne turns, and sleeps off your Nazi dreams,

but those other five scions you dreamt, who called you

Alcibiades instead of Dad, keep one eye open, distantly alert.

When Mom’s sleeping with the enemy, good kids stay awake.

Pamela Sumners

If you have any thoughts on this poem, Pamela Sumners would be pleased to hear them.